“Rayon is our most versatile fibre,” said one manufacturer in 1925. That same year, newspaper mogul Viscount Rothermere predicted that “at no distant date half of the clothing of the world will be made wholly or in part of rayon”. Indeed, the properties bestowed on rayon through different manufacturing methods and processes provided almost limitless variety.

Rayon fabric variety by Courtaulds’, including satins, lingerie jersey, and blended wool marocains [source]

Following its introduction, rayon yarns found diverse applications in dress fabrics, suitings, sweaters, lingerie, stockings, bathing suits, neckties & wraps, trimmings, millinery yarns, shoelaces, gloves, and linings. Artificial silk was even at the centre of a brief fad in 1915 for coloured wigs to match silk gowns. According to The American Silk Journal, “the artificial silk, on account of its possessing a greater lustre than hair, seems to be admirably suited for this purpose.”

By the 1930s rayon was available in a profusion of different fabrics and weaves - crepes, velvets, satins, jacquards, taffetas, shantungs, chamois, sharkskins, piqués, bouclés, gabardines, chiffons, voiles, and failles. Rayon could do anything the natural fibres could.

Rayon crepes, taffetas and failles in the Sears catalogue, 1934

“The versatility of rayon is well illustrated by Lanvin, for while employed in the most formal creations, rayon is also thoroughly approved for sports wear. The well made rayon sports costume, in addition to its clear, brilliant colours, is washable, holds its shape, and gives lasting service. Longchamps, Biarritz and the Riviera are familiar indeed with the sparkling gayety of rayon.” (The Mode and Rayon, 1928)

“I have been well pleased with rayon as a material […] and consider unquestionable its position in the mode” Jeanne Lanvin in an advertising collaboration with The Rayon Institute published in The New Yorker magazine, 1928

Characteristics

“You’re right… so right in blended fabrics of Viscose and Acetate Rayon” DuPont advert in Vogue magazine, 1950. [source: My Vintage Vogue]

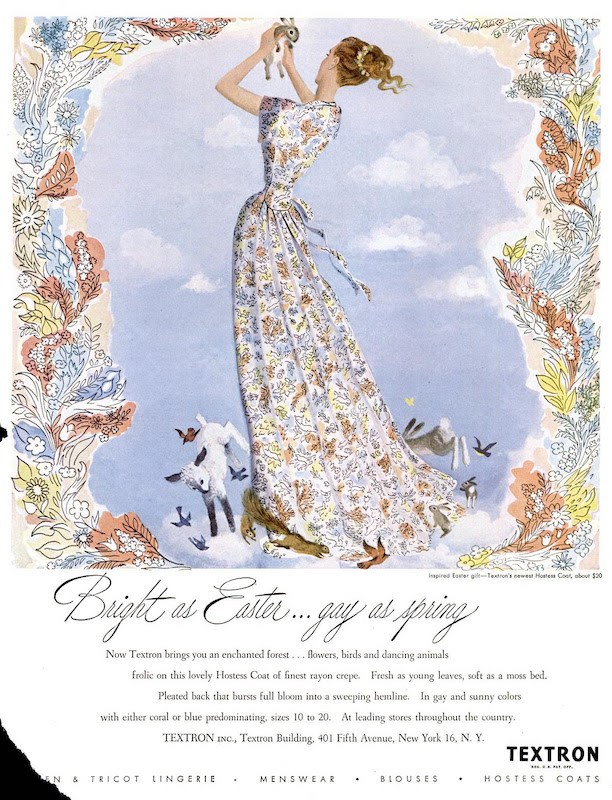

Rayon fibres are very flexible, giving rayon fabrics a soft hand and good draping quality. Acetate rayon is lustrous, supple and resilient, creating textiles that are soft to the touch and drape well in graceful folds. Rich satins and crisp taffetas show the fibre to excellent advantage. On movement of the wearer, acetate garments of taffeta produce “a gentle rustle that many associate with luxury type fabrics”.

“The flattery of it… the subtlety of it… the soft fluid drape of it” - 1950 advert for Celanese jersey [source: Pinterest]

Chiffon dress made from Enka rayon, 1950s [source]

Dyes and Colour Effects

Rayons (other than acetate) readily accept dyes due to their highly absorbent nature; indeed, the ability to attain “exquisite colours” as a result was a key selling point of early artificial silks. In a promotional campaign in 1929, the fashion house Callot Soeurs declared, “among rayon’s many contributions to the mode have been the variety and richness of its colours - we have made garments out of rayon fabrics and consider them unrivalled in beauty and grace.”

“Exquisite indeed the colour symphonies of rayon fabrics” - Callot Soeurs in an advertising collaboration with The Rayon Institute, published in The New Yorker magazine, 1928

Special dyes were developed for acetate since its water-resistance means it does not accept the dyes ordinarily used for cotton and rayon. This dye selectivity makes it possible to obtain multi-colour effects in fabrics made from a combinations of fibres. In a process known as cross-dyeing, yarns of different fibres are woven into a fabric in a desired pattern. After immersion in a dye bath, the pattern will appear in different colours or shades according to the distribution of the respective fibres.

Another dye method involves adding coloured pigments to the liquid chemical base prior to spinning, to produce coloured fibres. Such fibres are called spun-dyed or solution-dyed, and provide excellent colour fastness to sunlight and washing.

“Soft-textured ‘Celanese’ acetate beauty fabrics in glowing colours” c1950 [source: Pinterest]

Spun Rayon Textiles

Rayon fibre was initially produced as continuous filament, resembling cocoon silk. Extruded rayon fibres are very smooth and glossy, providing a “fascinating lustre” and imparting a “life and radiant richness” which beguiled early customers. However, it was when methods were developed to make the fibres matte or semi-matte, and to create spun rayon yarns, that rayon’s full potential really became apparent.

Cotton, linen and wool in their natural state comprise short, tufty fibres, which are then twisted together to make yarns. Rayon filaments can be cut into short lengths -- known as staple -- and spun into a yarn, lending the finished textile the slightly downy texture of cotton, linen or wool. It was reported in 1937 that “the use of this new type of rayon fibre is rapidly increasing because it produces fabrics that combine features of filament rayon, silk, wool, cotton, and linen, and are different from any of them.”

“In ‘Wool’ at only 2 coupons a yard!” spun rayons in Everywoman magazine, 1943

Rayon also blends extremely well with the natural fibres, for the best of both worlds. Combined with other fibres, rayon contributes such features as economy and softness of hand.

New Textures and Finishes

Rayon enabled innovative techniques and fabric finishes not possible with any other fibre. Rayon crepe was developed in 1927, and according to The Story of Rayon “it was found that rayon could be made to give a deeper pebble and a greater variety of crepe effects than is possible with silk”. The same author goes on to explain that in addition to “the standard crepes such as cantons and sheers, new designs appear each season running all the way from a flat crepe to the very rough type with a deep pebble, and even to quilted effects as in the matelaises.”

Grafton rayon crepes in Australian Women’s Weekly, 1939

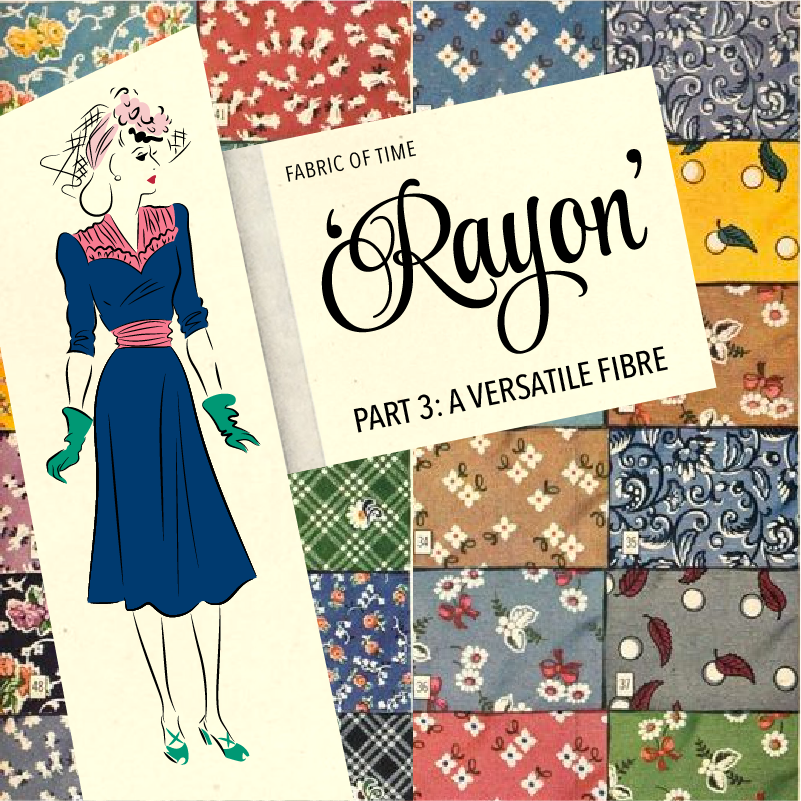

Textron rayon crepe in LIFE magazine, 1948

The thermoplastic nature of acetate rayon afforded further exciting opportunities. This characteristic made permanent pleating a commercial fact for the first time. This quality also made it an excellent fibre for moiré because once heat-set in place, the pattern is permanent, unaffected by water and therefore washable. Special patterns or surface textures can be embossed on acetate fabrics by pressing them against heated engraved metal plates.

“Celanese moirés present a beauty that is […] refreshingly novel… striking combinations of moiré with woven designs… moiré with embossed patterns… plain waterings, large or small, simple or sumptuous… and all are washable!”

“Celanese adds washability to the smartness of moiré... Lovely to the eye, lovely to the touch, these superb fabrics are miracles of practicality.” Advert for Celanese fabrics, 1929 [source: Pinterest]

“Celanese - the miracle dress fabric” in Sears, 1929

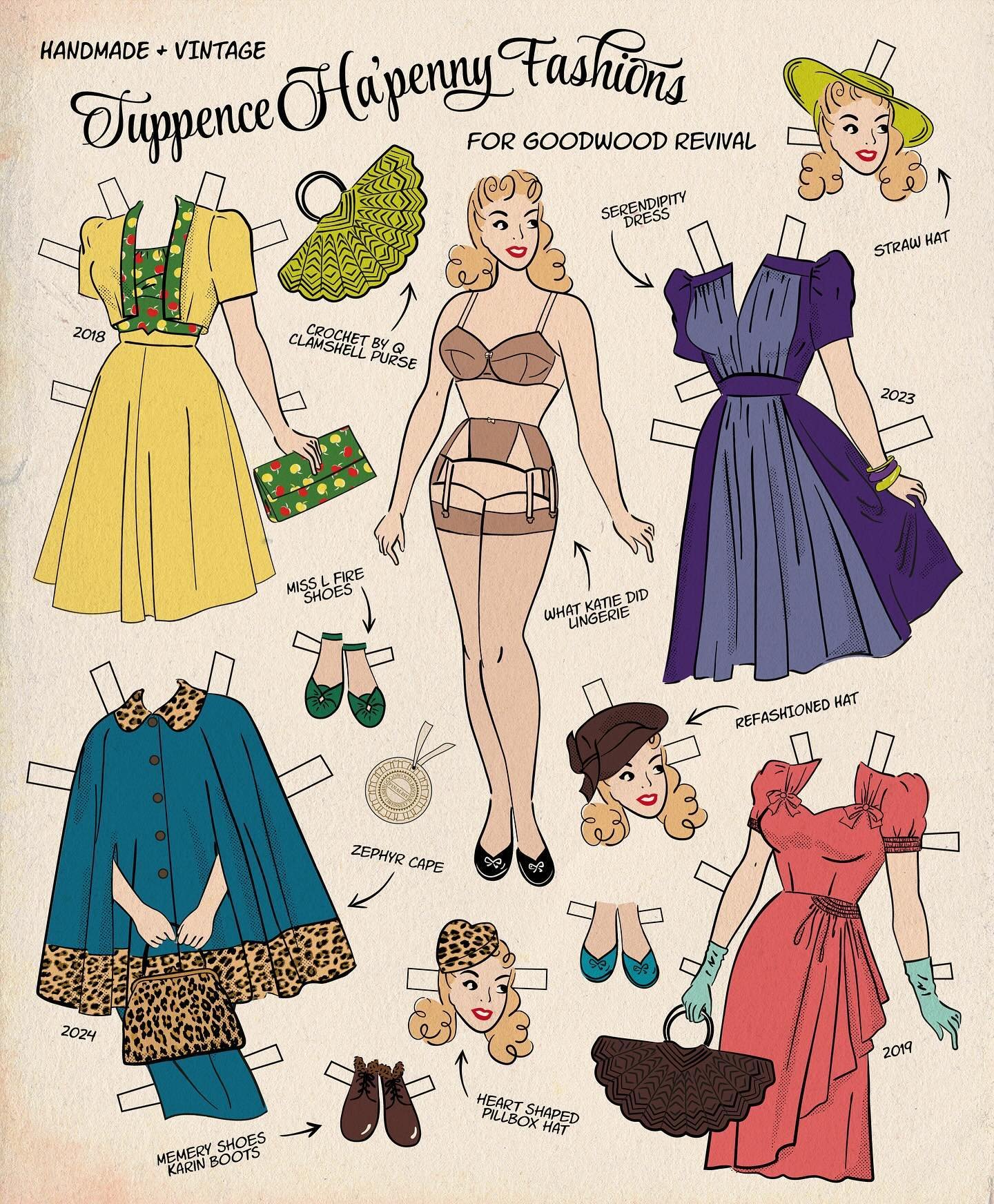

Millinery Rayons

Not to be limited to clothing, rayon’s utility extended to accessories and millinery materials. By varying the spinneret, viscose solution could be spun into filaments of different shapes and thicknesses.

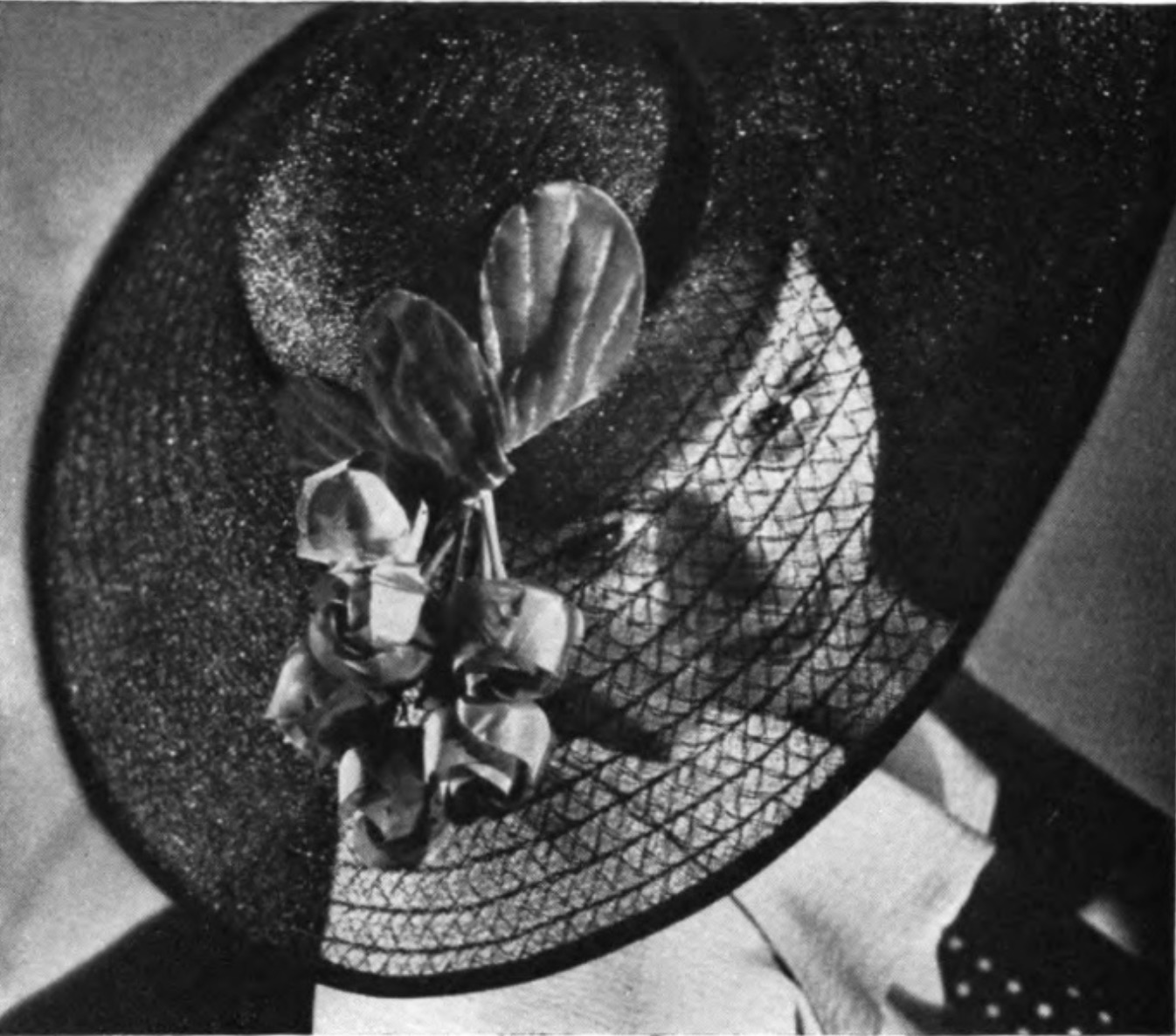

Monofil (artificial horsehair)

Monofil is extruded as a single filament, coarser than standard for textile yarns, intended to resemble horsehair. The filament is made into narrow braids which are used to form the delicate, lacy sun hats that were especially popular in the 1920s and 30s.

Monofil sun hat, pictured in The Story of Rayon, 1937

Visca (artificial straw)

Visca is spun similarly to Monofil, but instead of a round hole in the spinneret there is a narrow slit. The product is then drawn out as a fine ribbon resembling palm straw (raffia). It can be produced with either a bright, translucent lustre, or an opaque, matte finish. Visca is still manufactured today, and remains a popular material for ‘straw’ sun hats.

Visca straw hat by Betmar, Harper’s Bazaar, 1955 [source]

![Rayon fabric variety by Courtaulds’, including satins, lingerie jersey, and blended wool marocains [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1559158627020-LW5X9FR78QOFE625PMQ8/1928-courtaulds-rayon.jpg)

![“I have been well pleased with rayon as a material […] and consider unquestionable its position in the mode” Jeanne Lanvin in an advertising collaboration with The Rayon Institute published in The New Yorker magazine, 1928](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1559159006066-VC41O0STCVIM5EIZVD2Y/1928-newyorker-lanvin-rayon.jpg)

![“You’re right… so right in blended fabrics of Viscose and Acetate Rayon” DuPont advert in Vogue magazine, 1950. [source: My Vintage Vogue]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1561279728804-HD3L6FQ11MIBC9Q5XLON/1950b_rayon_full.jpg)

![“The flattery of it… the subtlety of it… the soft fluid drape of it” - 1950 advert for Celanese jersey [source: Pinterest]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1559160032458-KIEZEKUFAG4POOE6UO8X/1950-celanese-jersey.jpg)

![Chiffon dress made from Enka rayon, 1950s [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1559160048773-U5PM7U6GEDMDDKNCIS23/1950s-enka-rayon.jpg)

![“Soft-textured ‘Celanese’ acetate beauty fabrics in glowing colours” c1950 [source: Pinterest]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1559160924094-9IVRBT8VRPQW85O5E2VJ/1950s-celanese-colours.jpg)

![“Celanese adds washability to the smartness of moiré... Lovely to the eye, lovely to the touch, these superb fabrics are miracles of practicality.” Advert for Celanese fabrics, 1929 [source: Pinterest]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1559155829796-X2HFL7VOCFO7VRAWHT9N/1929-celanese-moire.jpeg)

![Visca straw hat by Betmar, Harper’s Bazaar, 1955 [source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59c4c09c64b05f30eddfb52e/1559165465935-6S2CGZW0TMVTFGDZA0HZ/1955-visca-harpersbazaar.jpg)